Predicting the Effects of Climate Change on Hurricanes: Thomas Knutson, Ph.D., a Senior Scientist in the US

Warmer oceans are shown to cause hurricanes to dump more rain. Sea level rise in Florida makes storm surge more destructive. And research also suggests that climate change may make it more likely for storms to rapidly intensify, which also happened to Ian. Such storms are dangerous because they get extremely destructive right before hitting land, giving people little time to evacuate.

Thomas Knutson is a senior scientist in the US and he says that they are attempting to use models to sort through some complicated relationships. He and his colleagues are joining the dots to predict how hurricanes are changing as the world warms.

The risks of climate change on storms were highlighted by the upcoming hurricane season. The latest climate research shows that climate change isn’t making storms to form in the Atlantic. Instead, a hotter Earth makes it more likely that the storms that do form will become big and powerful.

“We simulated fewer storms at the base level, but a greater fraction reaching Category 4 and 5 and making US landfall. Knutson says that the example of that is what we are seeing right now. This means that hurricane-prone regions in the US could see more storms with winds exceeding 130 mph, powerful enough to rip the roof off a building, uproot trees, and cut off power.

The Cost of Living in a Storm: The 2022 Atlantic Hurricane Season Is Almost Almost Necessary for Human Human Sufficiency

There is no cost of human suffering to be said regarding the brick-and-mortar costs. That’s almost incomprehensible. It’s not easy to know at the moment. That portion of the area is not accessible.

Roads and bridges have been laid to waste. Our article says homes and businesses are covered in wood and concrete on barrier islands.

Adam H. Sobel is an atmospheric scientist at Columbia University who studies extreme events and the risks they pose to human society. He’s the author of a book about Superstorm Sandy and the host of a show that explores similar storms. Follow him on Twitter: @profadamsobel. His opinions are his own in this commentary. CNN has more opinion on it.

In the end, the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season was among the most deadly and damaging in modern history. According to estimates by the reinsurance company, it was the third-most expensive season to date, with a total loss of $110 billion.

After that, almost nothing happened. We had the peak of the season in June and July, with few real storms, but no real damage. That was then. Fiona took down Puerto Rico’s power grid on September 18 (almost five years to the day after Maria had all but destroyed it) and then much of Nova Scotia’s in Canada, and then Ian, after knocking out power to all of Cuba, made landfall in Florida as a dangerous Category 4, one of the most destructive storms ever to hit the continental US, and decimated a wide swath of the Sunshine State.

The risk would remain the same or even decrease if the number of storms decreased fast enough. That good-news scenario seems unlikely to me, but it can’t be ruled out.

Some say the Atlantic increase is just the latest swing of a natural cycle. Before the lull in my youth, the 1950s and 1960s were very active, with many catastrophic US landfalls. (In the Northeast, for example, back-to-back hurricanes Carol and Edna struck in 1954, leading to the construction of storm surge barriers in Stamford, Connecticut, Providence, Rhode Island, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, all of which still operate today.)

When aerosols were cleaned up in the US and Europe in the 50s to 70s, the Atlantic warmed quickly and now is charged by greenhouse gas increases.

And new science darkens the prognosis for the Atlantic further. The last three years of La Niña conditions, when the eastern equatorial Pacific is cooler than average, are just part of a persistent trend in that direction over the last 50 years. Our climate models have failed to predict this, instead predicting that global warming should cause a trend toward more El Niño-like conditions.

Leaders from Pakistan and Kenya, Senegal and the Bahamas connected the dots between a hotter Earth and devastating floods, storms, heat waves and droughts. The United States is facing more severe hurricanes and wildfires, President Joe Biden said at the conference.

The World Weather Attribution, which establishes the link between weather and climate, concluded thatclimate change did not play any role in the flooding of Vietnam in 2020.

And federal forecasters, such as those at the National Hurricane Center, could also be effective messengers for climate information, says Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who studies extreme weather. “Confidence in these statements would be considerably higher,” he argues, if they were coming as part of forecasts and warnings that people already trust and turn to when a storm is bearing down.

It’s difficult to include climate in real-time weather warnings, according to Sarah Kapnick, the chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Kapnick has a background as a research scientist, and has worked on extreme-event attribution studies.

NOAA is currently reviewing how it communicates with the public about climate change, she says, in part because of a flood of interest from the public and from local officials who are grappling with more severe weather.

Pressed by CNN’s Don Lemon, Rhome responded, “I don’t think you can link climate change to any one event. On the whole, climate change may be making storms worse. But to link it to any one event, I would caution against that.”

Climate change may have caused Ian to drop at least 10% more rain than it would have without global warming according to a preliminary analysis by Wehner and other climate scientists.

Climate Change and the Last Days of Climate-Driven Storms: The Role of Winds, Grassmannians and Drifting Dwarfs

More support for electric vehicles as well as efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions are included.

It’s unclear how long those attitudes last after a climate-driven disaster. It is an active area of research to figure that out. “We have a window of time in which you may wish to help people better understand what the risks are and links to climate change,” Wong-Parodi says.

“I think that’s really important as we move forward, because it has implications for how we may want to communicate to the public about these types of events,” says Wong-Parodi.

Strong winds shift direction with altitude, giving rise to tornadoes that are fueled by warm, moist air.

When a series of tornados uproots trees, tore down infrastructure and kills dozens of people in Kentucky in December 2021, for instance, experts emphasized the historic nature of the outbreak but not the cause of climate change.

Think of a pair of dice, he said. If you change the value of one die to six it will give you two sixes which will increase the odds of you rolling the pair of dice. Although you can’t immediately attribute that value of 12 to the change you made, you just altered the probability of that event occurring.

High-Temperature El Nio will be the Hotest Year on Record in the Great Plains During the Last Five-Year Tornado Season

Todd Moore, associate professor and chair of the department of geosciences at Fort Hays State University, said that over the last few decades tornado frequency has increased in vast swaths of the southern Midwest and Southeast, while decreasing in parts of the central and southern Great Plains, a region traditionally known as Tornado Alley.

Scientists have warned that the rise in greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere is drastically changing the climate system, causing the jet stream — fast-flowing air currents in the upper atmosphere that influence day-to-day weather — to behave oddly.

This is backed by a 2021 report from the World Meteorological Organization that found an extreme weather event or climate disaster has occurred every day, on average, somewhere in the world over the last 50 years, marking a five-fold increase over that period and exacting an economic toll that has climbed seven-fold since the 1970s.

A global average temperature rise of 1.5°C is widely regarded as marking a guardrail beyond which climate breakdown becomes dangerous. Our once-stable climate will begin to collapse in earnest as it becomes all-pervasive, affecting everyone and insinuating itself into every facet of our lives. The figure was 1.2C in 2021, compared to 1850–1900’s average of 1.36C. As the heat builds again in 2023, it is perfectly possible that we will touch or even exceed 1.5°C for the first time.

Current forecasts suggest that La Niña will continue into early 2023, making it—fortuitously for us—one of the longest on record (it began in Spring 2020). Then, the equatorial Pacific will begin to warm again. Whether or not it becomes hot enough for a fully fledged El Niño to develop, 2023 has a very good chance—without the cooling influence of La Niña—of being the hottest year on record.

So what will this mean? I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see the record for the highest recorded temperature—currently 54.4°C (129.9°F) in California’s Death Valley—shattered. This could well happen somewhere in the Middle East or South Asia, where temperatures could climb above 55°C. The heat could exceed the blistering 40°C mark again in the UK, and for the first time, top 50°C in parts of Europe.

One of the worst-affected regions will be the Southwest United States. Here, the longest drought in at least 1,200 years has persisted for 22 years so far, reducing the level of Lake Mead on the Colorado River so much that power generation capacity at the Hoover Dam has fallen by almost half. Upstream, the Glen Canyon Dam, on the rapidly shrinking Lake Powell, is forecast to stop generating power in 2023 if the drought continues. The Hoover Dam could be next to follow suit. Together, these lakes and dams provide water and power for millions of people in seven states, including California. The breakdown of this supply would be catastrophic for agriculture, industry, and populations right across the region.

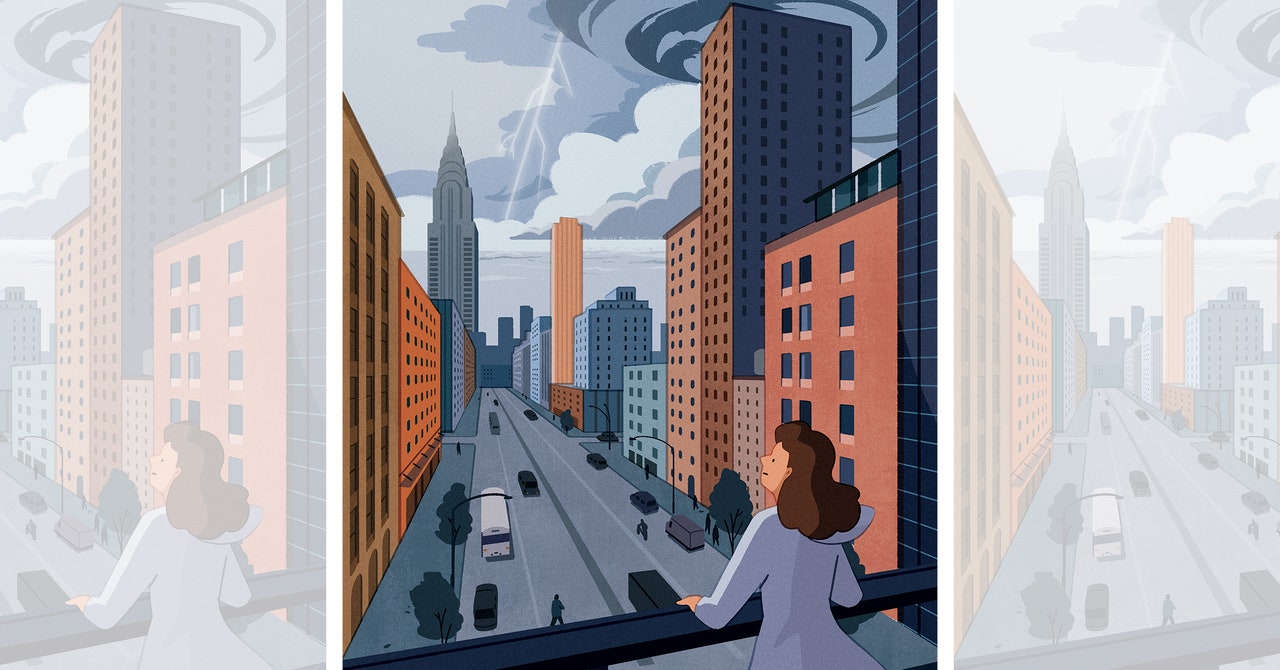

La Niña tends to limit hurricane development in the Atlantic, so as it begins to fade, hurricane activity can be expected to pick up. Extreme heating of the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico surface waters is possible due to the higher global temperatures expected in the future. If super-hurricanes strike land, this would favor the formation and persistence of powerful winds, storm surge and hurricanes that could wipe out a major US city. Direct hits, rather than a glancing blow, are rare—the closest in recent decades being Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which made landfall immediately south of Miami, obliterating more than 60,000 homes and damaging 125,000 more. Hurricanes today are both more powerful and wetter, so that the consequences of a city getting in the way of a superstorm in 2023 would likely be cataclysmic.

In early September, a lot of people who live in hurricane-prone parts of the United States started noticing that it had been an eerily quiet summer. On average, there are 14 storms each year in the Atlantic between June 1 and December 1.

“It was actually, kind of, fear and dread,” says Jamie Rhome, the acting director of the National Hurricane Center, thinking back on the quietest part of the Atlantic hurricane season. “I felt like people were letting their guard down.”

The Effects of the Ocean Water Wall on Global Storms and Their Implications for Storm Surveillance: A Comment on Rhome

The wall of ocean water that storms push onto land was the main source of flooding. The more power the storm has, the more water it pushes inland. Rhome says that a rising sea level makes storm surge worse.