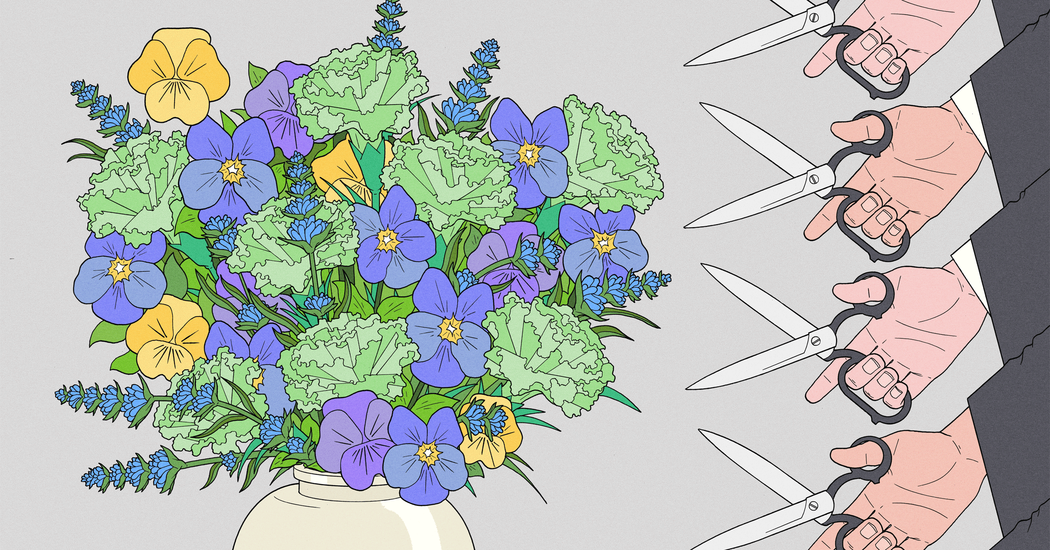

The Supreme Court rules that a designer cannot make a website celebrating the wedding of a gay couple, and it violates First Amendment rights against compelled speech

The Supreme Court has ruled that a graphic designer can’t be required to make a website celebrating the wedding of a (possibly hypothetical) gay couple, saying it would violate First Amendment protections against compelled speech. It is a decision that is unsurprising, but it could also be a factor in the fight over online moderation.

It is not clear if a specific couple will have to change their wedding plans after this. Smith went to court after he received a request for services from a couple called “Stewart” and “Mike” but the one in question is already married to a woman and never made the request. The incident was seemingly crafted to let the conservative-heavy Supreme Court carve out protections for belief-based discrimination along the lines of the Masterpiece Cakeshop case.

The idea of the case being about speech is called profoundly wrong and reactionary in the Dissenting opinion delivered by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. “The law in question targets conduct, not speech, for regulation, and the act of discrimination has never constituted protected expression under the First Amendment,” Sotomayor writes. The constitution does not allow us to refuse service to a group.

This year, however, the new conservative supermajority reached out in an unusually aggressive manner, agreeing to decide a case in which nobody had yet filed a claim of discrimination.

On Friday, the court ruled against the state and for the web designer in a decision that could have profound consequences in Colorado and 29 other states that have laws requiring businesses open to the public to serve everyone, regardless or race, religion, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation.

I have two moms, one a musician, the other a professor and ordained minister. The three of us spent every summer of my early childhood at my grandparents’ house in rural New York, where my musician mom ran a music festival. One day she walked into a local cafe to find a sign bearing an antigay slogan: Homosexuals will burn in hell, we remember it saying. The cafe, it turned out, was owned by the Twelve Tribes, a fundamentalist group known for teaching that gay people deserve to die. After seeing the sign, my mom was deeply shaken. My mom was angry. “Who are they to say we can’t be here?” she remembers thinking. “It was very much a sense of invasion.” I felt scared at one point. We never went back to that cafe.

Last fall, for my first major assignment in law school, I wrote a mock brief for the respondent’s side in 303 Creative, defending the Anti-Discrimination Act as if I were the attorney representing Colorado. I wasn’t expecting the project to bring up family memories, but I thought it might feel personal.