Status of the Mission NEA Scout: A Journey to the Moon, and Tests of Space Missions for Humans and Spacecrafts

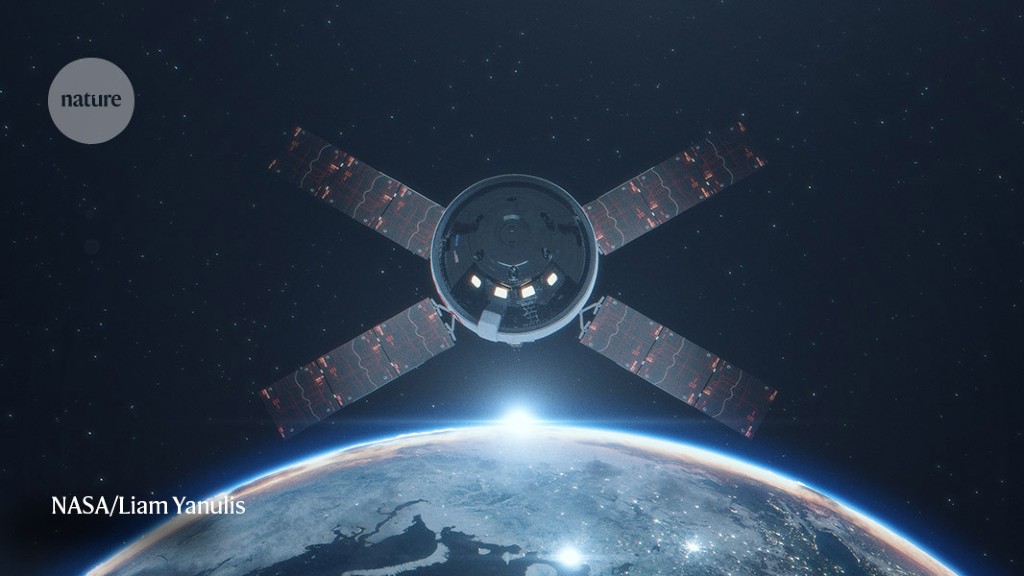

In the past three weeks, NASA’s new spaceship has traveled to the moon and most of the way back in a test. It will face its biggest challenge since it was part of the Artemis I mission, surviving a fiery re-entrance through Earth’s atmosphere and a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean on 11 December. In the end, it will test a re-entry tactic that has never been used before by a passenger vehicle.

The farthest space vessel intended to carry humans has ever traveled is the farthest out of the moon. For now, the capsule is only carrying inanimate, scientific payloads.

Some small problems, such as occasional issues with the star-track navigation system and the electrical system that ferries power from the solar panels to the capsule, are being fixed by engineers.

Images from the journey to date show the sun glinting in reflected sunlight and an Earth that looks like a blue dot or the Moon looming grey. NASA has also released pictures of the capsule’s interior, where a mannequin known as a moonikin watches over control panels and a small stuffed Snoopy toy floats around as an indicator of zero gravity. Flight director Judd Frieling, also at Johnson Space Center, said that more video footage would be released soon, and that a low-resolution livestream from Orion is now available whenever communication bandwidth allows.

The Artemis I launch also carried ten small satellites into space, most of which have scientific missions. Of those, eight have been reported to have established communications with controllers after launch. But one of them, a miniature Japanese Moon lander named OMOTENASHI, began tumbling out of control and was declared lost by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Of the two whose status is unknown, one is a solar sail designed to fly past a near-Earth asteroid. That mission, known as NEA Scout, successfully deployed after the Artemis I launch but has not been heard from since.

The small spacecraft, which was launched from Earth in June and had some problems in September, entered its own lunar space on 13 November. It is going to be used by a NASA lunar space station called Gateway to fly over the moon’s poles.

NASA released a selfie taken by the Orion capsule and close-up photos of the moon’s crater-marked landscape as the spacecraft continues on the Artemis 1 mission, a 25-and-a-half day journey that will take it more than 40,000 miles beyond the far side of the moon.

The Artemis I mission launched November 16, when NASA’s beleaguered and long-delayed Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket vaulted the Orion capsule to space, cementing the rocket as the most powerful operational launch vehicle ever built.

As of Thursday afternoon, the capsule was 222,993 miles (358,972 kilometers) from Earth and 55,819 miles (89,831 kilometers) from the Moon, zipping along at just over 2,600 miles per hour, according to NASA.

The moon will travel in the opposite direction from which it travels around Earth as a result of being at high altitude above the lunar surface.

The burn is slated to take place at 4:30 p.m. on Friday and will air on NASA Television at 4:52 pm.

Orion is on a precisely engineered path to return to Earth off the coast of San Diego, California, at 9:40 a.m. local time on its designated return date. “We’re targeting for a very thin slice of atmosphere,” said Nujoud Fahoum Merancy, NASA’s chief of exploration mission planning, during an agency broadcast on 5 December.

The capsule is not carrying astronauts. But one day, it’s supposed to. NASA has a plan to eventually return humans to the Moon, but they need to make sure that it goes off without a hitch.

For re-entry to go just right, the capsule will need to slow down from around 40,000 kilometres per hour when it hits the top of Earth’s atmosphere, to just 32 kilometres per hour when it drops into the Pacific. The brunt of that braking energy will be borne by Orion’s heat shield, which will endure temperatures of around 2,800 °C — hotter than what’s needed to make steel.

In the center of the space vehicle is where four astronauts will sit when it flies again on the Artemis II mission. NASA is not testing any life-support systems on this flight, so temperatures in the crew cabin are a bit chilly, around 10–12 °C.

What is being tested are the effects of space radiation on simulated humans. The capsule holds two faux human torsos; one of them is strapped into a vest to protect it against radiation, and the other is not. The magnetic shield protecting the planet against harmful solar energy protects it from the radiation we get from the torsos. Some experiments are experimenting with the effects of radiation on organisms. None of these data can be collected and studied until after splashdown.

The capsule will jettison part of its cover around 7 kilometres above Earth’s surface and then deploy 11 parachutes in rapid sequence, to slow the capsule for splashdown. The capsule will be pulled onto the Well deck of the waiting ship.