Dodo rediscovered: bringing back woolly mammoths and Tasmanian tigers through genomic DNA decoding

When sea levels were low, the ancestors of the dodo lived in Southeast Asia, and once sea levels rose, they went to India where they became isolated.

The sailors brought with them pests like rats, and practices like hunting. They doomed the dodo, which showed no fear of humans, to extinction in the space of just a few decades.

The dodo is something that has been brought back by some scientists who want to incorporate advances in ancient genome technology and synthetic biology. They hope the project will open up new techniques for bird conservation.

We are in the middle of an extinction crisis. And it’s our responsibility to bring stories and to bring excitement to people in way that motivates them to think about the extinction crisis that’s going on right now,” said Beth Shapiro, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Shapiro is the lead paleogeneticist at Colossal Biosciences, a biotechnology and genetic engineering start-up founded by tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm and Harvard Medical School geneticist George Church, which is working on an equally ambitious projects to bring back the woolly mammoth and the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger.

The first step in the project, fully decoding the dodo’s genomes from ancient DNA, was completed by Shapiro.

Colossal: A Monkey Launch for Synthetic Biology, and First Results from a Case Study in Caloenas nicobarica

The approach involves removing primordial gems cells from an egg, cultivating them in the lab and editing the cells with the desired genetic traits before injecting them back to an egg at the same developmental stage, she explained.

However, Shapiro said that perfecting these synthetic biology tools will have wider implications for bird conservation. The techniques could allow scientists to move specific genetic traits between bird species to help protect them as habitats shrink and the climate warms.

If we can find a way to give immunity to a population, and show how the genetic changes underlying that immunity affect the ability to fight off a disease, we might be able to transfer that to other species.

Mike McGrew, a senior lecturer and personal chair in avian reproductive technologies at the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh, described the project as a “moon launch for synthetic biology.” His work involves turning commercial egg-laying hens into surrogates for rare chicken breeds revived from frozen primordial germ cells.

Colossal’s plan starts with the dodo’s closest living relative, the iridescent-feathered Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica). The company plans to culture primordial germ cells from developing Nicobars. Colossal’s scientists would edit DNA sequences in the PGCs to match those of dodos using tools such as CRISPR. These genes would be used to create chimeric animals that can make dodo-like eggs and sperm. Something resembling a dodo could be produced by these.

Whether or not Colossal and its team of scientists are ultimately successful in their quest to bring back the dodo and other extinct creatures, de-extinction projects, and the technological breakthroughs they may generate, have investors excited. Colossal said Tuesday that it had raised an additional $150 million and that the total amount of funding it had raised was $225 million.

What the dodo did in the seventeenteeth century did Mauritius lose, but didn’t it die? A voice of the bird Hume

Critics, however, say the vast sums involved could be better put to use protecting the 400 or so bird species, and many other animals and plants, that are listed as endangered.

The predators that were threatening the dodo in the seventeeth century haven’t disappeared, whereas most of its habitat has. Shouldn’t we be spending this money on restoring habitat on Mauritius to prevent species from going extinct?

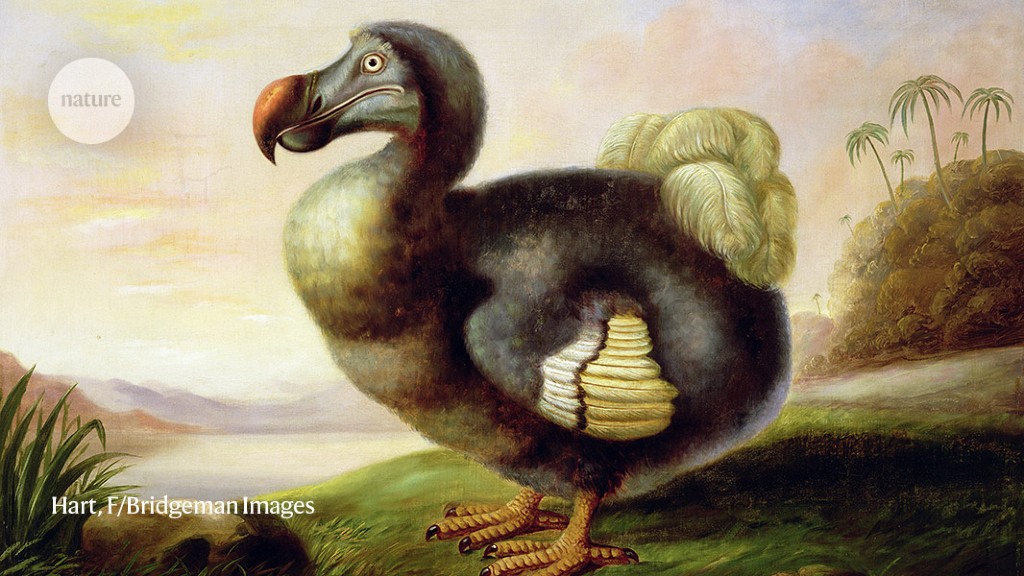

Hume said there’s very little known about the dodo and lots of myths surround the creature. Even the origin of its name is a mystery, though he thinks it stems from the sound of the call the bird was said to have made — a low-pitched pigeon-like coo.

“Flight is very (energetically) expensive. Why bother maintaining it if you don’t need it? You can become big when you become flightless because the fruit and food is on the ground. That’s what the dodo did, it just got bigger and bigger and bigger,” Hume said.

According to a digital 3D model of the bird Hume developed based on a skeleton from the Durban Natural Science Museum in South Africa, the dodo once stood around 70 centimeters (2.3 feet) tall and weighed about 15 to 18 kilograms (33 to 39 pounds).

Dodos in avian environments have a difficult time getting their genetic genomes, says Thomas Jensen, a conservationist at the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation

Back in the 1600s, before the first dinosaur fossils were widely known, “the concept of extinction didn’t exist. Everything was created by God. The idea that something could be erased was not something anyone in our day thought of.

He said that it was an amazing bird at the time of discovery. “They disappeared rapidly. There was nothing left when people wanted to know more about them.

“It’s incredibly exciting that there’s that kind of money available,” says Thomas Jensen, a cell and molecular reproductive physiologist at Wells College in Aurora, New York. I am not sure if the end goal they are going for is something that will be doable in the near future.

Chicken embryos are more receptive to other birds in comparison to eggs, and Jensen’s team has created chimeric chickens that can produce quail sperm. But he thinks it will be far more challenging to transfer PGCs — particularly heavily gene-edited ones — from one wild bird into another.

Tom Gilbert, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Copenhagen, who also advises Colossal, expects the dodo genome to be of high quality — it comes from a museum sample he provided to Shapiro. But he says that finding all the DNA differences between the two birds is not possible. The ancient genomes are filled with errors and gaps, and they were cobbled together from short pieces of degraded DNA. He published research last year that showed gaps in the dodo’s genome that have changed the most since the rat’s extinction.

The number of edits that need to be made could be reduced by focusing on certain changes in the genetic material. But it’s still not clear that this would yield anything resembling a wild dodo, says Gilbert. “My worry is that Paris Hilton thinks she’s going to get a dodo that looks like a dodo,” he says.

A large bird that can act as a surrogate is a problem, says Jensen. Dodo eggs are larger than Nicobar pigeon eggs, and you can not grow a dodo inside of a Nicobar egg.

The director at the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation is excited about the attention de- extinction could bring to the cause. He says that they would like to embrace it.