Understanding The First Two Episodes: Black Athlet Walker Embarrassment of a Black Senator, Jon Ossoff

America’s evolution is not possible without understanding how blackness impacted citizenship, dignity, wealth, poverty and punishment. In this way, the first two episodes form a couplet that work more powerfully in tandem.

And that is reason enough to fully acknowledge the pain left behind by Walker’s candidacy, and even more reason to celebrate Warnock’s win as more than a partisan victory for the Democratic Party. Realizing the dream of multiracial democracy is a step in the right direction.

Walker was not a member of the Republican Party but he was a friend of Trump and had a well-known past as an athlete.

The GOP embrace of Walker is a tragedy. Walker’s behavior on the campaign trail included incoherent ramblings about movies and farm animals, nonsensical asides that went nowhere and dancing in front of overwhelmingly White audiences in bizarre scenes that recalled the minstrel shows of the Jim Crow era. The whiff of the Jim Crow era’s objectification of Black men as intellectually feeble but physically powerful grew stronger as Walker’s humiliating campaign continued to showcase the GOP’s failure to understand or connect with Black voters.

On January 5, 2021, Warnock became the first Black person elected to the US Senate from Georgia in American history. Alongside Jon Ossoff, who became the first Jewish senator ever elected from the state, these historic victories were overshadowed by the tragic circumstances that commenced the next day.

Tyre Nichols, 29, is the latest black man to be charged with the aggravated kidnapping and murder of a Memphis skater

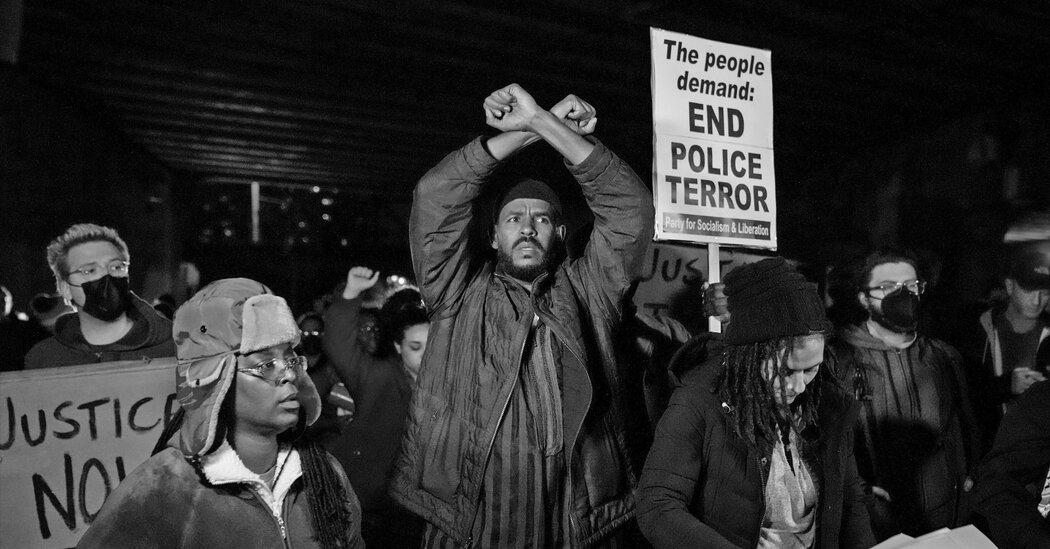

This month, Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Memphis father, became the latest Black man to join a horrific line of abuse that connects that moment 55 years ago to right now. Five Memphis police officers have been charged with the aggravated kidnapping and second-degree murder of Mr. Nichols, an avid skateboarder and photographer who worked the second shift at FedEx. The officers beat him. He said, “I’m just trying to get home.” And he called out for his mother (as George Floyd did in 2020), unbeknown to her at the time, even though she was at their house less than a hundred yards away.

The author is a retired Montgomery County, Maryland, police captain. She is the founder of The Black Police Experience, which promotes the education of the intersection of law enforcement and the Black community. She is an assistant professor of criminal justice in Washington, DC, as well as at Montgomery College in Maryland. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion at CNN.

To see Black officers embracing brutality and aligning themselves with a police subculture that calls for loyalty to even the most heinous of police behaviors — such as beating subjects who run from the police — is beyond devastating, especially since modern day policing in this country can be traced back to slave patrols, and abuses within the criminal justice system continue to result in the over-policing and death of Black people.

Nichols, who struggled to his feet and ran off, was found minutes later. Police body camera and surveillance footage released Friday showed the officers striking Nichols with a baton, kicking him in the head and repeatedly punching him before propping him against a police car.

The officers were milling around, without any one providing aid in the critical minutes after the beating. The preliminary results of an autopsy commissioned by attorneys for his family are that he died after a severe beating and it took an ambulance more than 20 minutes to get to the scene.

Based on my 28 years of experience as a former police officer and captain, it was clear to me that the officers lacked supervision, showed little professional maturity and escalated a situation into what would eventually become a deadly encounter through gross negligence and a complete disregard for human life.

The Black community is very traumatised by the damage done to them by the murder charges against the five officers. Members of the Black community often expect Black officers to be their vanguard.

The association’s current stance is unusual. It did not defend the arrested officers outright or say that they were just doing a difficult job that required them to make split-second decisions – responses we’ve come to expect from police unions that so often help shield officers accused of misconduct from accountability.

George Floyd’s death in 2020 has prompted calls for more police officers to be hired, partially because of the fear of rising crime. President joe bianca proposed funding for 100,000 new police officers as part of his safer America plan and a bill includes $324 million in funding to hire more police officers.

I know from experience that crime prevention can be achieved by trusting police and community relations, rather than by adding more police officers. There can be no trust when there is over-policing of disadvantaged communities with suppression units such as the SCORPION unit, which were formed to protect communities – not terrorize them. On Saturday, the Memphis Police Department announced that it would not be renewing its affiliation with the SCORPION unit.

The federal policing bill that bears George Floyd’s name failed to pass in the Senate and efforts to end qualified immunity, a judicial doctrine that protects police officers from being held personally liable for violating a person’s rights, have not succeeded in Congress.

States and local jurisdictions have tried to tackle police misconduct through new policies and legislation. It is not unusual for law enforcement to conduct training and revise policy over and over, but there are still too many deaths at the hands of police.

This article has been modified to accurately reflect the writer’s experience; she has 28 years of combined experience in law enforcement, not just as a captain.

The 1619 Project: Black Americans, Black Power, and Democracy in the Land of the Free, the Frozen, and the Untouchable

The New York Times multimedia project, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, is recreated in the first two episodes of “The 1619 Project.”

As the first two episodes of “The 1619 Project” make dramatically clear, “the relentless buying, selling, insuring, and financing” of Black people “would help make Wall Street and New York City the financial capital of the world.”

The stories “The 1619 Project” shares with viewers are fundamentally American ones, where Blacks take center stage as among the most fervent, patriotic and resilient stewards of democracy in the nation’s history.

The New York Times Sunday Magazine special issue, the multimedia educational social media support materials and the bestselling anthology have been provided by the documentary series.

Speaking autobiographically, Hannah-Jones argues, “no people had a greater claim to the American flag” which her military veteran father proudly hung outside her childhood home in Waterloo, Iowa, than Black people. She recounts how her childhood alienation from American history was interrupted by a Black high school history teacher who explained the meaning of 1619 for Black American and American history –the year the first enslaved Africans were brought to the shores of Virginia aboard the English White Lion ship.

Hannah-Jones describes it in the first episode as the “challenges for democracy ahead,” and one “The 1619 Project” does a wonderful job telling that story. Her framing puts modern-day voter suppression tactics, ranging from disallowing voters from receiving food and water on long lines to allowing anyone to object or challenge a voter’s ballot in states like Georgia in crucial historical context that links past and present.

This violence paralleled Reconstruction’s bright spots for decades, reaching a fever pitch in 1898 the Wilmington Massacre, the first successful political coup in American history – organized by vengeful White racists against Black political leaders who were slaughtered, humiliated and forced to flee the city.

The episode takes a close look at both the racial and sexual reproductive realities Black women have faced throughout American history. During racial slavery, Black women were raped by White owners who then enslaved their own children to add more value to their fortunes.

Our racial identities being listed on certificates of birth and death are more than bureaucratic signposts. They serve as markers of destiny and signifiers of future wealth and prosperity for some and punishment and premature death for others.

We eavesdrop on the recordings that were once slaves conducted by the Works Progress Administration. Laura Smalley, a formerly enslaved Black woman, recalls that plantation owners would “breed them like they was hogs or horses, something like that, I say.”

This is an incredibly painful history that needs to be confronted in our own time, and it is more necessary than ever. It also may help to explain how a Black woman as rich and famous as Serena Williams almost died from complications after giving birth to her daughter Olympia.

The principle that all Black lives should matter is established by the Black Power pioneers. “In our minds, what it really meant was Black empowerment,” recalls Vern Smith, a veteran Black journalist who was a student at San Francisco State, where the push for Black Studies began. “It seems quaint when you look back at it, but the sense of inferiority that had been pushed down on people for generations was just not thought about until that moment…If you are a 20- or 25-year-old Black person today and you call yourself Black or African-American, it seems just like the most natural thing in the world to do. I guess that’s a testament to the success that Black Power had in terms of making people not feel bad about themselves and to really embrace who they were.”

The top civil rights leaders from America descended on Mississippi in the summer of 1966 to march in support of equal rights. They were making their way from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi to carry on a solo voting rights march begun by James Meredith, the Black activist who had integrated the University of Mississippi three years earlier. Meredith had been shot by a White supremacist and hospitalized with severe bullet wounds.

He counted the number of times that he had been imprisoned in the South since joining SNCC. By the time he was out, he was prepared to implement a defiant new slogan that a SNCC comrade, Willie Ricks, had been testing.

From the start, the media assumed the worst about the Black Power slogan. Was it Carmichael who was saying to take power by force and violence? Three days after the speech, Martin asked if Carmichael would be booked for his first national TV appearance.

The next day, a short Associated Press story describing the scene was picked up by more than 200 newspapers across America. Overnight, the Black Power Movement was born.

The Black Power generation was prescient when they looked into the weaknesses of urban policing and the limits of racial integration preached by King. As children of the Great Migration, they knew all too well the heartbreak of Blacks who had left everything behind in the South in pursuit of a false promise of physical security, fair housing and job opportunities in the North.

Despite the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Carmichael recognized that registration alone wouldn’t be enough to protect poor Blacks in the Deep South, where police allowed the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize with impunity. He spent the previous year in backwater Alabama organizing blacks to create a political party that would allow them to become sheriff and other local officeholders with a symbol that was popular with poor sharecroppers.

That, in turn, made them an inviting target for J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, who launched a war of sabotage and dirty tricks aimed at preventing any of Panther leaders from emerging as a “messiah” who might rally young Blacks. Within two years, the party’s founders had been in jail or in exile, and were not even able to serve as more than radical poster boys.

When the Panthers first donned their famous leather jackets and berets and posed with rifles and handguns, it was to advertise their plan to take advantage of California’s “open carry” gun laws to create armed civilian patrols to monitor the Oakland police.

As if to prove the Panthers’ point, however, the summer of 1966 brought a series of clashes between police and urban Blacks that set off riots in Chicago, Atlanta and the San Francisco neighborhood of Hunters Point. White support for the civil rights agenda fell sharply when those uprisings were used as a means to push the “Black Power” slogan. In a Newsweek poll, Whites suddenly opposed even nonviolent Black protest by more than two-to-one.

The leaders of SNCC initially refused to allow an ultranationalist group to expel White members, but after a staff retreat where there were many drug users, they relented. After only a year in charge of the SNCC, Carmichael stepped down to make way for a successor with more inflammatory rhetoric and less charm named H. Rap Brown.

There was another cycle of decline for the Black Panther. After winning release from prison and getting the support of a few well-known authors, Eldridge Cleaver began writing a book, “soul on Ice”, in which he advocated the use of armed revolution.

A second lesson is to prepare for a backlash if there is any temporary progress. The last moment of the civil rights movement, in 2020, was seen as a turning point in the push for police reform, as well as calls to defund the police.