Melville House, Penguin Random House, and Skyhorse: Publishers for the Jan. 6 Capitol-Report-Publish-Capitol-attack

Melville House co-founder Dennis Johnson is one of six book publishers who will be printing the report on the attack on the Capitol. He is not sure what’s inside the report, it’s a mystery to him.

“It’s a public document, paid for by the citizens of the us,” said Johnson. He’s waiting, “just like everybody else,” for it to show up on the government’s website, most likely as a PDF.

Of course the Jan. 6 report is entering a very different America. The publishers’ plans reflect that. The forward from MSNBC anchor Ari Melber will be included in theHarperCollins version. Penguin Random House’s will come with one by Congressman Adam Schiff. Skyhorse is publishing theirs with a foreword from Darren Beattie, an ally of former president Trump whose website regularly publishes election denial conspiracies. Johnson chose to make MelvilleHouse’s version 888-282-0465 888-282-0465 888-282-0465 888-282-0465. “We think the document should speak for itself,” he said.

It will take a lot of time to get a book from PDF to page. Publishers must deal with the layout and typesetting. A bunch of redactions can be a whole other can of worms. Publishers are hoping that the House releases are easy to find. Johnson believes that the work is a public good, in that it will make the public record more accessible, unlike a hard- to-read document on a government website.

The Senate investigated the CIA’s secret program of detaining and interrogating prisoners. It dropped unassumingly, a few days before Christmas. It appeared, just like that. Johnson believed that the quiet release was part of the Senate’s attempt to “squash the impact of the report.”

Source: https://www.npr.org/2022/12/16/1143422586/jan-6-panel-report-publish-capitol-attack

The 9/11 Report: What we’ve learned from the work of Ernest May and his advisor to the Commission on the Public Works,” Phyllis Johnson, Jr

It was a document that we worked around the clock on. He said that the staff had to work for 24 hours a day and over a week to make the book.

He said most government reports were like the instruction manual to a microwave oven. They’re tedious, stilted, dry and stuffed with technical language. But the 9/11 report was different. Ernest May was a senior advisor to the commission and he worked with them to craft a narrative. “He wanted them to be storytellers,” said Warren.

“And what most surprised readers was that they employed elements that are commonly found in fiction, like suspense and foreshadowing and irony and metaphor. And as a result, readers were captivated not only by the contents of the report, but by its literary artistry,” he said.

But while Johnson does see it as a moral duty to publish the report, there is one thing that’ll stop him from putting it out at all. If it’s a 6,500 page report with 100,000 pages of transcripts, I’m going to let someone else publish it. “I’m going to make Penguin live up to their promise to publish it.”

The Cheney Committee on Domestic Violence and Crime: Public Outrage, Public Concerns, and Political Dilemma in the Final Days of the Report

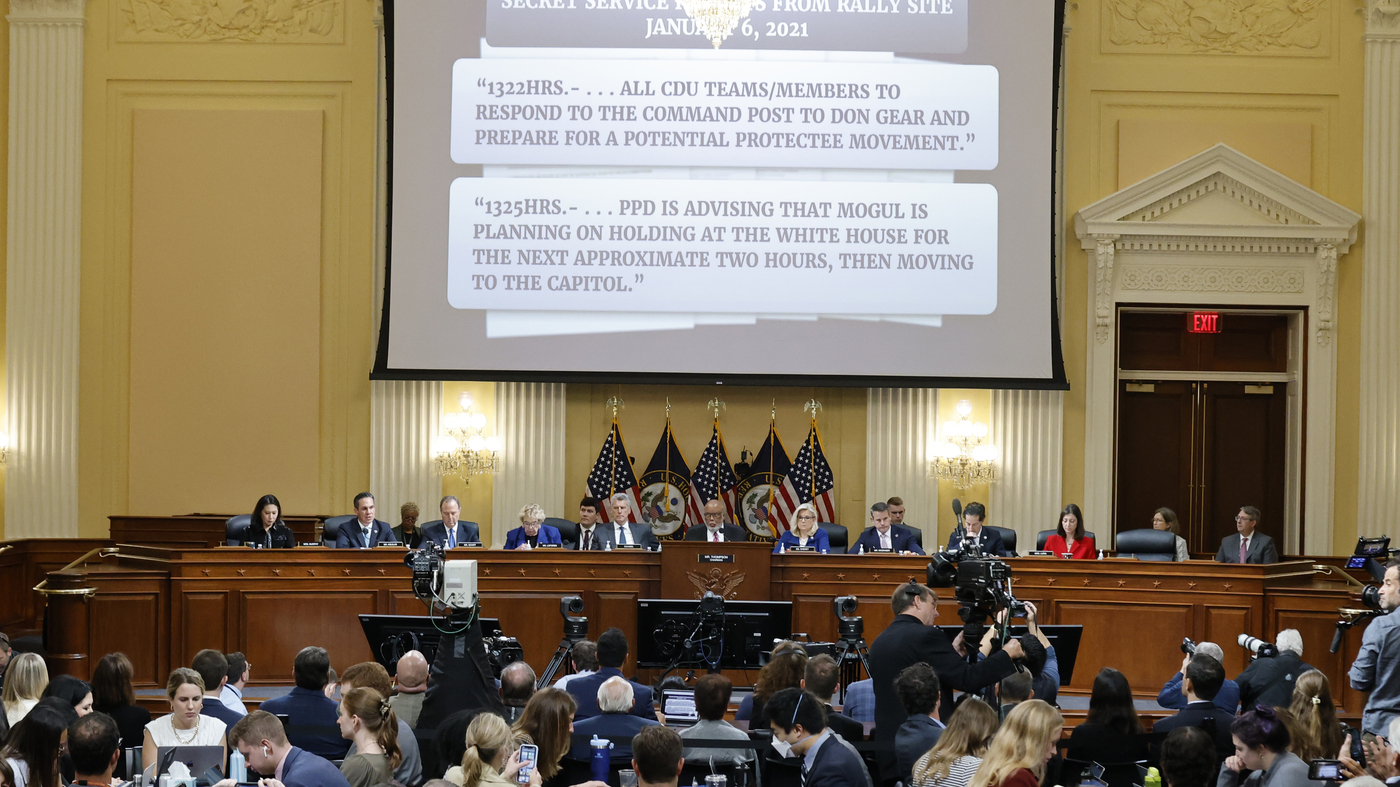

With its expiration date of Jan. 3 looming, the committee spent its final months in a frenzy of activity occasionally marred by bitter contentiousness. Cheney, unsurprisingly, was at the center of the conflicts. One point of disagreement was over her insistence that the committee make criminal referrals of Trump; John Eastman, the lawyer who advised Trump that Pence could overturn the election; and others to the Justice Department, which initially struck Lofgren as an empty symbolic gesture, until Thompson stepped in and helped form a consensus around Cheney’s position.

Far more controversial internally was Cheney’s adamant position that the committee’s final report focus primarily on Trump’s misconduct, while marginalizing the roles of violent domestic actors, their financial organizers and their sympathizers in law enforcement. Current and former staff members expressed their outrage to news outlets after learning of the decision. Some members aligned themselves with the dismayed staff, while other members agreed with Cheney that some of the chapters drafted by different aides did not measure up to the committee’s standards. Still, it seemed excessive to some on the committee when Cheney’s spokesperson claimed to The Washington Post on Nov. 23 that some of the staff members submitting draft material for the report were promoting a viewpoint “that suggests Republicans are inherently racist.”

Senior staff members had resigned under less than amicable circumstances throughout the committee’s tenure. The senior technical adviser and former congressman left for a different job after he was suspected of leaking material to the news media. In September, the former federal prosecutor Amanda Wick and others left over disagreements about the committee’s direction. And in November, similar disgruntlement compelled Candyce Phoenix, who led the Purple Team investigating domestic extremists, to step back from her duties even as the final report was nearing its closing stages.

The writing of the report was messy. There was great confusion about how the report would be written and what role different people would play in putting it together. After months of dysfunction and infighting, Thomas Joscelyn, a writer brought on board by Cheney who at one point was told he would not be working on the draft after all, ended up submitting drafts that would constitute significant portions of the report. Concerns were raised that the final product could read like one.

The final days of working together brought one factor to the fore. Four of its nine members were either defeated during the 2022 midterms (Cheney and Luria) or decided to retire from Congress (Kinzinger, whose district had been redrawn to favor Democrats, and Murphy). The last duty that the four departing members were given was to make a report that would be posted on the committee’s website as they were no longer living in the Washington offices. The committee would send the text to the U.S Government Publishing Office, where it would be printed, with colorful graphics and engaging fonts not typically found in a government publication.

How many would ever read the document, and be convinced by the evidence it held, would be unknowable, but also beside the point. The Government Publishing Office is a hoary federal institution that was created by a congressional resolution in 1860 and began operation in 1861, after Lincoln’s inauguration and just before the country descended into civil war. It printed the Watergate White House transcripts in 1974 and the Sept. 11 Commission Report in 2004. Soon it would also place the Jan. 6 committee and its findings in the American historical record, as the lasting artifact of a congressional inquiry premised on the belief that if democracy was sacred, then so was the duty to investigate an attack on it. The committee was told by the judge that the congress had the highest obligation to conduct these hearings. The hearings have been historic and could never be duplicated.

The magazine has a writer named Robert Draper. He is the author of, most recently, “Weapons of Mass Delusion: When the Republican Party Lost Its Mind.”

Philip Montgomery takes pictures of the broken state of America. His monograph of photography was published earlier this year.