The Oscars Push To Leslie: Why a Little-Time Independent Film Has a Big Heart, Not a Black Role. Why Social Media Makes Push Public

It’s, frankly, a strange tale – one that began in October with the limited release of a small-time independent film called “To Leslie,” about what happens when a single mother wins the lottery and runs out of money. Riseborough plays the lead role and is praised by critics as having one of the best performances of her career.

“It’s not really a one-person-replaces-another situation,” Schulman says of Riseborough’s nomination. “But of course, it brought up all these issues of equity and representation at the Oscars, and opened up this question of does a Black actress like Danielle Deadwyler have the network of support within the industry that Andrea Riseborough [does]?”

But some big-name Hollywood figures agreed with critics and stars like Gwyneth Paltrow, Amy Adams, Kate Winslet and Jennifer Aniston were vocal in their support for Riseborough on social media (sometimes in eyebrow-raising similar language) and via other venues – like Q&As and screenings.

Meanwhile, on Twitter, other actors have posted almost identical statements supporting the film, calling it a “small film with a giant heart.” Some have likened it to a copy-and-paste job.

An actor has gone public before with an Oscars push on their own. Ten years ago, actressMelissaLeo posed for her “For Your Consideration” advertisements. Leo at the time was nominated for best supporting actress for her role in 2010’s “The Fighter.”

Industry-watchers have noted that soliciting votes is often done to level a playing field – in this case, bring attention to a small-budget, little-known film. Social media makes push public, rather than one done behind closed doors.

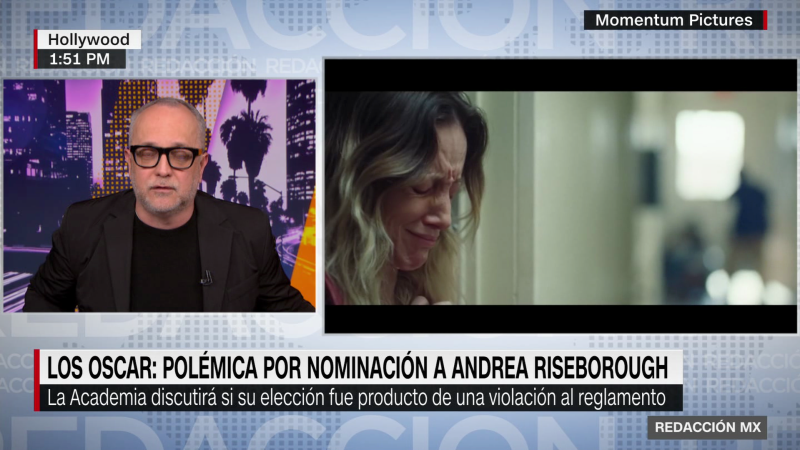

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Announces Andrea Riseborough’s nomination for best actress for her performance in the independent drama To Leslie

Thought-to-be contenders Danielle Deadwyler (“Till”) and Viola Davis (“The Woman King”) were among those who were shut out of the best actress category this year.

The Academy’s diversity problem has long been discussed and dissected. Risesbrough is not to blame for the snubs, but her campaign behind her display shows how much of an advantage it is to have famous White friends.

Christina Ricci, star of the Emmy-nominated show “Yellowjackets,” called the Academy’s decision to review the procedures “very backward,” in a now-deleted Instagram post.

Whether Riseborough’s nomination will actually be overturned is hard to say. There is precedent – in 2014, composer Bruce Broughton received an Oscar nomination for the title song from “Alone Yet Not Alone” and was later disqualified over his campaign.

They are joined in the category by Riseborough, as well as the other two actresses, Gwyneth Paltrow and Academy Award Nominees, Daniel Day-Lewis and Catherine Tate.

British actress Andrea Riseborough will get to keep her Oscar nomination for best lead actress for her performance in the independent drama “To Leslie,” the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced on Tuesday.

“However, we did discover social media and outreach campaigning tactics that caused concern,” the statement added. “These tactics are being addressed with the responsible parties directly.”

The Academy’s statement did not specify which rules may or may not have been broken in the course of the campaigning that took place on the film’s behalf.

The Academy strives to create an environment where votes are based on artistic and technical merits of the eligible films and achievements.

In his new book, Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat and Tears, Schulman writes about the behind-the-scenes battles viewers don’t see on Oscar night. In the early decades of its existence, the Academy of Motion Pictures was roiled by anti-communist hysteria and blacklists. More recently, the #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite movements have challenged the Academy to confront its own institutional biases and blind spots.

It’s a mistake to see the awards as just a way to measure artistic merit or worth, according to Schulman. Instead, he says, “There are a million other factors that go into who gets nominated and who wins.”

Schulman says the effort to garner an Oscar nomination is similar to a political campaign: “You have campaign strategists and publicists and people who spend the entire year working on campaigns, strategizing, placing ads, entering films in film festivals and sort of positioning movies and appealing to particular Academy members.”

In Hollywood, the Oscars ceremony is held in a theater and broadcasted around the globe. It’s a long way from the first Academy Awards, which were handed out during a brief, 15-minute ceremony, following a dinner in a banquet room of the Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles on May 16, 1929.

“What fascinates me about the very first Oscars is even at the beginning … “Hollywood was in a rough spot,” he says. “For instance, The Jazz Singer, the groundbreaking talkie that basically killed off the silent movies had just come out and it was given an honorary award because the Academy felt it couldn’t even compete with all the other nominees, which were silent films. All of the nominees for the second Academy Awards had sound.

What I tried to do in the book is take certain years of the Oscars and put them on the couch and psychoanalyze them. And these moments of transition and these moments of instability are always so fascinating. … When La La Land won a few years ago you could sense it, and that’s because of the crazy envelope mix up. It’s only one movie. It’s just a single victory, but it means a lot. You can sense the culture kind of changing in this tectonic way.

In 2016, for the second year in a row, all of the 20 acting nominees were white. And an activist named April Reign had started a hashtag the year before, which was, “#OscarsSoWhite they asked to touch my hair,” and that got some pick-up in 2015. It went crazy in 2016; it was very popular. There was a lot of attention given to the whiteness of the people who do the voting in the Academy and the fact that they are male.

It has made a difference. One of theunderappreciated things about the reforms is that the Academy became more international. And I think you start to see that reflected in a win like Parasite a few years ago. Hollywood has become less of a barrier for the Academy’s assessment of movies. But of course, the controversy has not died down. This year we have the best actress category. This is a great year for Asian nominees: Michelle Yeoh and Hong Chau, all the people from Everything Everywhere All at Once. There is no black actress that has been nominated. Since Halle Berry won the best actress award in 2002, there haven’t been any other people of color who’ve been nominated. So I think this is not a problem that’s been solved. It’s a battle similar to the larger issue in American life over representation and inclusion.

The Hollywood Paradigm: Saving Private Ryan, Shakespeare in Love and the New Academy of Arts: The Twilight of Hollywood and the Rise of DreamWorks

He also had a real gift for sort of creating stunts that would get publicity. For instance, when the English Patient was out, he staged an entire evening at a town hall in New York City with people reading from the book. … He would come up with new ways to create humanitarian campaigns in his movies. He brought Daniel Day-Lewis’ movie to Washington and screened it for senators.

Spielberg’s film Saving Private Ryan was intended as a tribute to his father’s generation. And his father had fought in the war. In the summer of 1998 it came out. It was a gigantic success, a critical darling, and it was presumed to be the frontrunner for best picture for many months. And then in December, along came Shakespeare in Love, from Harvey Weinstein’s Miramax. It was very different than the other kind of movie. It was frothy and fun and clever and romantic, and it was about art, not war and love, not death. The Oscar leading up to exhaustion has been a feature of many, many years. And so people were suddenly interested in this new dynamic. And then what Weinstein did with Miramax was push every conceivable angle he could with this movie. There were many ads. He was throwing parties.

They were absolutely furious. They started complaining to the press about everything Miramax was doing. Harvey Weinstein denied. And the people who worked for him didn’t necessarily know what he was doing all the time. And so they felt that they were just being smeared by DreamWorks. The people thought Saving Private Ryan would win the Oscar, due to the hostile relationship between the two studios. Spielberg was the winner of the best director. Shakespeare in love won the best picture. It was an explosion of shock and anger.

The Academy was founded in early 1927, and it was the brainchild of Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM. The 36 people who founded the company were all connected to the powerful people of the silent Hollywood era. And their original rhetoric was extremely utopian. They saw themselves as a League of Nations for Hollywood. And much of what they were saying is that they wanted to create harmony and resolve disputes. They were doing that side of things. The subtext of that is that Hollywood was not unionized at the time except for the technical craftspeople. And so the Academy, in a way, was created to preempt Equity or some other organizing body from organizing the creative professions. …

It got to the point where the president of the Academy at the time, the director, Frank Capra, realized how toxic this all was. And he loved the Academy Awards. And he basically said, OK, the Academy is no longer going to do any of that stuff, any of that negotiating conflict resolution, anything having to do with economics or contracts, we’re just not going to do it anymore. And so they really shed a lot of their original purpose. The only thing that everyone in Hollywood liked about the Academy was the Oscars.