Detecting ROH from ancient genomes with haploidity, pileupCaller and hapROH46. Application to accelerator mass spectrometry dating

The results of our population genetics show that 15 ancient individuals are called Ancient Rapanui and they are in fact part of the study.

We used Plink and hapROH46 to detect ROH. We used a model of haploidity called the e-model and random_allelims to find ROH. To do so, we used pileupCaller (https://github.com/stschiff/sequenceTools) following ref. 103 to generate pseudohaploid calls at the 1240K sites with output in eigenstrat format, as required by hapROH. Following ref. 104, we ran PLINK with the following command to detect ROH in imputed ancient genomes and high-coverage present-day genomes: plink –bfile input –homozyg –homozyg-kb 500 –homozyg-gap 100 –homozyg-density 50 –homozyg-snp 50 –homozyg-window-het 1 –homozyg-window-snp 50 –homozyg-window-threshold 0.05 –out output. We restricted this analysis to transversion SNPs and filtered imputed genotypes (MAF > 1% and GP ≥ 0.99). In the Supplementary Information section 10 we describe the analyses in detail and present validation results. 25–27 and Supplementary Tables 17–21.

Accelerator mass spectrometry dating was undertaken at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (University of Oxford, UK) and Bristol Radiocarbon Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (University of Bristol, UK), with measurements undertaken using MiCaDaS accelerators. We used established methods to pretreat bone and extract collagen for accelerator mass spectrometry dating. Stable isotope analyses of carbon and nitrogen were performed using the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. We used a mixture of the radiocarbon likelihoods and the mix_Curve method to correct for marine excretion and offset the local ocean resources in our model.

Ancient Rapanui: Improving whole-genome sequencing data with GLIMPSE and contamMix84. Imputation validation and identification of present-day human DNA contamination

Efforts to reconcile the relationship between ancient and present-day Rapanui was one of the questions the project tackled. The researchers hope that eventually the repatriating of the remains will happen.

We used GLIMPSE v1.1.131 to impute whole-genome sequencing data using the 1000 Genomes v5 phase 3100,101 as a reference panel following ref. 99. A detailed description of our imputation validation is presented in Supplementary Information section 5 and validation results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 6–10 and Supplementary Table 3.

We determined the chromosomal sex of the Ancient Rapanui individuals by examining the depth of coverage ratio on the X chromosome and the autosome (Supplementary Fig. 2). The authenticity of the data was assessed by looking at the length distributions and misincorporation patterns of the reads. In addition, we computed type-specific error rates using ANGSD v0.93083 (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). We estimated the proportion of present-day human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) contamination using contamMix84 on the basis of a majority rule consensus for each individual and an alignment of 311 worldwide mtDNA sequences85. We estimated the proportion of present-day human nuclear DNA contamination in XY individuals using contaminationX86 on reads with a mapping quality ≥30, bases with quality ≥20, sites with depth between 3 and 20 and the HapMap CEU allele frequencies87. A detailed description of the authentication procedures is included in Supplementary Information section 3.

We examined 11 petrous bones and four teeth from a collection of 15 individuals that were kept in the Muséum national d’ Histoire naturelle in Paris. We presented our research after meeting with representatives of the Rapun community, who are located on the island. The two commissions voted in favor of us continuing with the research.

Evolution of ancient genomes from descendants of Rapa Nui dispels the historical narrative of colonial collapse and precolonial contact with Indigenous populations

There are Illumina adaptor sequence, leadingN bases, trailing quality-2 runs and collapse reads over 11 bases, and we used AdapterRemoval to trim them. Collapsed reads were mapped on their own without seeding. 81. We retained mapped reads with a mapping quality greater than 30, removed PCR duplicates using picard MarkDuplicates (http://picard.sourceforge.net), carried out local realignment using GATK82 and computed the MD tag and extended BAQ for each read using the samtools calmd command. A detailed description of the data processing procedures is presented in Supplementary Information section 3 and mapping statistics are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Now, a study of ancient genomes from descendants of these voyagers has answered key questions about the island’s history, dispelling the idea of a population collapse hundreds of years ago, and confirming precolonial contact with Indigenous Americans.

The theory that the early Indigenous inhabitants of Rapa Nui — also known as Easter Island — ravaged its ecosystem and caused the population to crash before the arrival of Europeans in the early eighteenth century was popularized in the 2006 book Collapse, by geographer Jared Diamond, but some other scholars have since criticized that theory.

The analysis published on 11 September in Nature 1 is the final nail in the coffin of the collapse narrative says Kathrin Ngele, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Correcting the image of Indigenous people is the purpose.

After settling Rapa Nui by around ad 1200, ancient Polynesian people developed a flourishing culture famous for its hundreds of colossal stone statues, called moai.

When Europeans first reached the island in 1722, they estimated that it had a population of between 1,500 and 3,000 people and found a landscape denuded of the palm-tree forests that would have once covered the island. By the late nineteenth century, the Indigenous population, called the Rapanui, had dwindled to 110 people, owing to a smallpox outbreak and the kidnap of one-third of the inhabitants by Peruvian slave traders.

The ‘ecocide’ theory, that a pre-contact population of 15,000 or more plundered the once-pristine island’s resources, has been challenged by researchers who have questioned humans’ role in deforestation and its effects on food production, as well as the large estimates for the population.

The ecocide theory as well as another lingered hope for Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, a population geneticist of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland and Vctor Moreno-Mayar, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen.

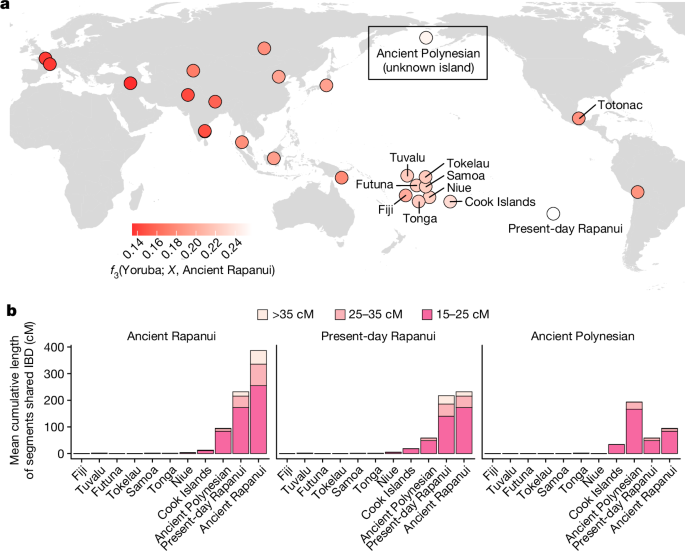

The ancient and modern genomes have information about how a population has changed over time. When the population is small, segments of DNA shared between individuals — which are inherited from a common ancestor — tend to be longer and more abundant, compared with DNA segments from periods when numbers are higher.

Translating these trajectories into actual population numbers is not straightforward, but further modelling suggested that the genetic data are not consistent with, for example, a drop from 15,000 to 3,000 people before the eighteenth century. Malaspinas says there isn’t a strong collapse. We are quite sure that it did not happen.

According to Keolu Fox, a genome scientist at the University of California, San Diego, there is no surprise to Polynesian people that Rapanui reached the Americas. He says that they are confirmation something we already knew. “Do you think that a community that found things like Hawaii or Tahiti would miss a whole continent?”

Malaspinas and her colleagues were given approval to conduct the study from the land use and cultural heritage committees. Malasipinas regrets that they asked for their permission to sample the remains in Paris. “I would do things differently if I had started the project today,” she says, adding that her team was prepared to shelve the work if the committees had said no.

Nägele, who works in Polynesia, thinks the researchers did a good job of engaging with people in Rapa Nui. But she adds that scientists should have a stronger role in pressuring foreign institutions to return Indigenous remains to their place of origin.