Kicking the Artemis I Rocket: Preparing for a Launch in Puerto Rico with Low Pressure and Unnamed Cyclots

NASA will attempt to get the Artemis I mission off the ground again Friday, just as the hulking rocket at the heart of the plans to return humans to the moon is heading back to the launchpad.

Liftoff of the uncrewed test mission is slated for November 14, with a 69-minute launch window that opens at 12:07 a.m. Time. On NASA’s website, the launch will be live.

The Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket began the hours-long process of trekking 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) from its indoor shelter to Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida late Thursday evening.

The rocket had been stowed away for weeks after issues with fuel leaks that thwarted the first two launch attempts and then a hurricane rolled through Florida, forcing the rocket to vacate the launchpad and head for safety.

The Artemis team again is monitoring a storm that could be heading toward Florida but feels confident to move ahead with rollout to the launchpad, said Jim Free, associate administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate.

Mark Burger, the launch weather officer with the US Air Force, said the unnamed storm would slowly move northwest early next week because it is located near Puerto Rico.

“The National Hurricane Center just has a 30% chance of it becoming a named storm,” Burger said. The models are very consistent on low pressure development.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2022/11/04/world/artemis-sls-rollout-scn/index.html

The First Artemis Mission Off the Ground: A Ground Test using Supercold Propulsor Seals and Easible Loading Procedures

Returning the 322-foot-tall (98-meter-tall) SLS rocket to the nearby Vehicle Assembly Building, or VAB, gave engineers a chance to take a deeper look at issues that have been plaguing the rocket and to perform maintenance.

In September, NASA raced against the clock to get Artemis I off the ground because there was a risk of draining batteries essential to the mission if it spent too long on the launchpad without liftoff. Engineers were able to recharge or replace batteries throughout the rocket and the Orion spacecraft atop it as they sat in the VAB.

The Artemis I mission is to pave the way for more missions to the moon. After takeoff, the Orion capsule, which is designed to carry astronauts and sits atop the rocket during liftoff, will separate as it reaches space. It’ll fly empty for this mission, apart from a couple of mannequins. The capsule will travel to the moon for a few days before heading back to Earth.

But getting this first mission off the ground has been trying. The SLS rocket ran into problems when it was loaded with a lot of liquid hydrogen and it leaked a lot. A faulty sensor gave inaccurate readings as a rocket attempted to cool the engines down so they are not shocked by the temperatures of its fuel.

NASA has been working to resolve the issues. The Artemis team decided to ignore the faulty sensor’s data in order to mask it. And following the second launch attempt in September, the space agency ran another ground test when the rocket was still on the launchpad.

The purpose of the demonstration was to test the seals and use new loading procedures for the supercold propellant, which is what the rocket will experience on launch day. NASA said the test met all its objectives, despite it not going as planned.

The Space Launch System Artemis I Launch of a Large Scale Spacecraft on a Mission to the Moon, and Other Mission Control Issues

Before the SLS, NASA’s space shuttle program, which flew for 30 years, endured frequent scrubbed launches. SpaceX’s Falcon rockets also have a history of scrubs for mechanical or technical issues.

“I do want to reflect on the fact that this is a challenging mission,” Free said. We do a flight test because we have seen challenges getting our systems to work together. The things can’t be modeled. We are learning by taking more risk on this mission before putting crew on there.

After several delays, NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) spacecraft lifted off on November 16th and catapulted the Orion capsule on a mission around the moon. The capsule went close to the moon’s surface before flying beyond it for about a week. About halfway through the mission, the spacecraft reached 268,563 miles away from Earth, the furthest any human-rated spacecraft has traveled.

An uncrewed test flight for the new capsule by NASA and the European Space Agency is intended to see how it holds up during deep space travel. So far, the spacecraft, which could carry astronauts to the Moon in as little as two years, has been doing about as well as mission controllers could have hoped, Hu said: “We have seen really good performance across the board.”

The electrical system that ferries power from the solar panels to the capsule is intermittent and causes occasional problems, and engineers are trying to fix it.

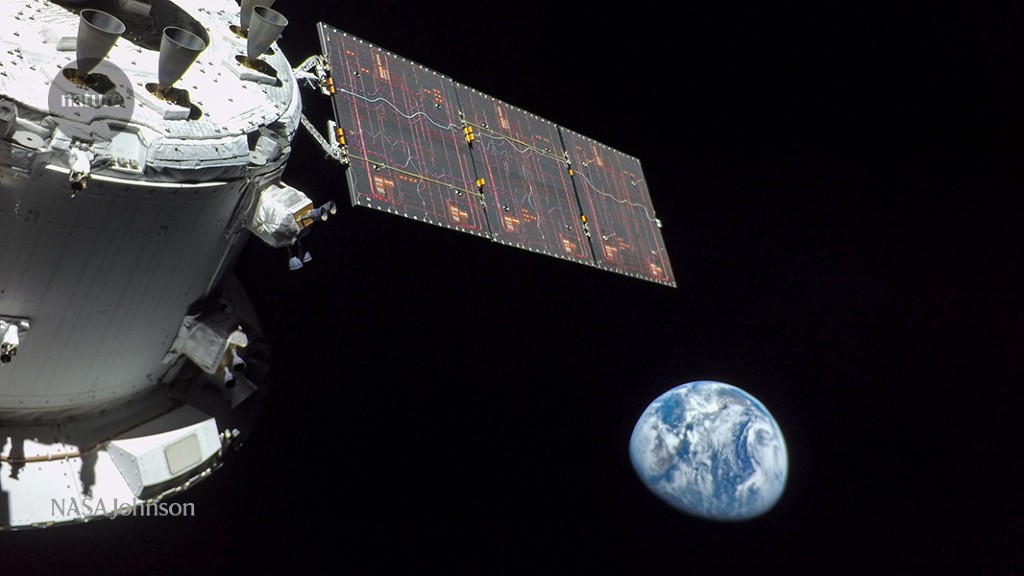

Images from the journey so far show Orion glimmering in reflected sunlight in deep space, occasionally with Earth appearing as a pale blue dot in the distance, or with the Moon as a looming grey presence. NASA has also released pictures of the capsule’s interior, where a mannequin known as a moonikin watches over control panels and a small stuffed Snoopy toy floats around as an indicator of zero gravity. Flight director Judd Frieling, also at Johnson Space Center, said that more video footage would be released soon, and that a low-resolution livestream from Orion is now available whenever communication bandwidth allows.

The Artemis I launch also carried ten small satellites into space, most of which have scientific missions. Eight of the 25 have established communications with controllers after launch. The Japanese Moon landers fell out of control and were declared lost by the Japan Aeronautical Exploration Agency. One of the two that is unknown has a solar sail that is supposed to fly past an asteroid. After the Artemis I launch, Scout NEA successfully deployed, but it has not been heard from since.

Separately, a small spacecraft called CAPSTONE, which launched from Earth in June and encountered some problems in September, entered its own lunar orbit on 13 November. A trajectory meant to be used by a NASA lunar space station is being flown over the Moon.

Orion’s latest selfie — taken Wednesday, the eighth day of the mission, by a camera on one of the capsule’s solar arrays — reveals the spacecraft giving angles with a bit of moon visible in the background. The close-ups were taken on Monday when the moon’s surface was passed about 80 miles above the earth.

As of Thursday afternoon, the capsule was 222,993 miles (358,972 kilometers) from Earth and 55,819 miles (89,831 kilometers) from the Moon, zipping along at just over 2,600 miles per hour, according to NASA.

Orion is now about a day from entering a “distant retrograde orbit” around our closest neighbor — distant, because it will be at a very high altitude above the lunar surface, and retrograde, because it will circle the moon in the opposite direction from which the moon travels around Earth.

According to NASA, the burn is scheduled to take place on Friday at 4:52 p.m.

Orion is on a precisely engineered path to return to Earth off the coast of San Diego, California, at 9:40 a.m. local time on its designated return date. “We’re targeting for a very thin slice of atmosphere,” said Nujoud Fahoum Merancy, NASA’s chief of exploration mission planning, during an agency broadcast on 5 December.

The capsule is not carrying any humans. But one day, it’s supposed to. NASA needs to get Orion home safely to keep on track with its Artemis programme, which aims to eventually return humans to the Moon’s surface.

The capsule reached a speed of about 24,500mph as it returned to Earth, and its heat shield was very hot at 5,000 degrees. Orion traveled a total of 1.4 million miles through space over the span of 25.5 days.

Orion’s interior — where four astronauts will sit the next time it flies, on the Artemis II mission — is currently staffed by one mannequin and a floating Snoopy doll. The crew cabin temperatures are a bit chilly at 10 C because NASA is not testing any life-support systems.

What is being tested are the effects of space radiation on simulated humans. The capsule holds two faux human torsos; one of them is strapped into a vest to protect it against radiation, and the other is not. Detectors on the torsos measure radiation dosage as Orion flies out of and back into Earth’s magnetic shield, which protects our planet against harmful solar energy. Other experiments inside Orion are measuring the effects of radiation on organisms including yeast. The data cannot be collected or studied until after the splashdown.

The capsule will first detach itself from its cover and then deploy 11 parachutes in rapid succession to slow the capsule down for a splashdown. Recovery teams on the waiting ship will then pull the capsule on board its hangar-like ‘well deck’.

Mike Sarafin, Artemis mission manager, stated during a press conference on Thursday that the Mission is on track and has achieved some bonus objectives. He went on to say the main objectives for the day of splashdown are to test Orion’s re-entry and to practice the retrieval of the spacecraft from the ocean.

“Skip entry gives us a consistent landing site that supports astronaut safety because it allows teams on the ground to better and faster coordinate recovery efforts,” said Joe Bomba, Lockheed Martin’s Orion aerosciences aerothermal lead, in a statement. NASA’s primary contractor isLockheed.

“We’re not out of the woods yet. The next big test is the heat shield,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told CNN in a phone interview Thursday, referring to the barrier designed to protect the Orion capsule from the excruciating physics of reentering the Earth’s atmosphere.

The heat caused the air molecule to ionize and created a 512 minute communications cutoff, according to Judd Frieling.

What will the Orion Spacecraft tell us about the return of the Apollo 11 spacecraft? A message to the NASA astronauts about their safe return from space

The advantages of skipping entry are similar to those of astronauts who experience less crushing forces during spaceflight.

While there were no astronauts on this test mission — just a few mannequins equipped to gather data and a Snoopy doll — Nelson, the NASA chief, has stressed the importance of demonstrating that the capsule can make a safe return.

Upon return from this mission, Orion will have traveled roughly 1.3 million miles (2 million kilometers) on a path that swung out to a distant lunar orbit, carrying the capsule farther than any spacecraft designed to carry humans has ever traveled.

On its trip, the spacecraft captured stunning pictures of Earth and, during two close flybys, images of the lunar surface and a mesmerizing “Earth rise.”

We expect things to go wrong and that isn’t a plus. Nelson said that when they do go wrong, NASA knows how to fix them. But “if I’m a schoolteacher, I would give it an A-plus.”

If the Artemis I mission is successful, NASA will dive into the data collected on this flight and look to choose a crew for the Artemis II mission, which could take off in 2024.

The spacecraft finished the final stretch of its journey, closing in on the thick inner layer of Earth’s atmosphere after traversing 239,000 miles (385,000 kilometers) between the moon and Earth. It splashed down at 12:40 p.m. ET Sunday in the Pacific Ocean off Mexico’s Baja California.

The capsule is now bobbing in the Pacific Ocean, where it will remain until nearly 3 p.m. ET as NASA collects additional data and runs through some tests. That process, much like the rest of the mission, aims to ensure the Orion spacecraft is ready to fly astronauts.

All the heat that came and went on the capsule is being tested. We want to make sure that we characterize how that’s going to affect the interior of the capsule,” NASA flight director Judd Frieling told reporters last week.

The Artemis 1 Mission Launched in Portland, On Dec. 16, 2001 at 5:42 AM U.S. The First Launch Mission

As it embarked on its final descent, the capsule slowed down drastically, shedding thousands of miles per hour in speed until its parachutes deploy. The vehicle was travelling at an average speed of 20 miles per hour in the moment when it splashed down.

Now that Orion’s back on the ground, NASA will start capturing data from the sensor-equipped mannequins on board so it can get ready for future missions involving humans. The second Artemis mission is scheduled for twenty four years from now and will try to get humans back on the Moon.

The agency is now one step closer to getting humans back on the moon.

“We watched the scene from the deck and saw the three full main parachutes go off,” said Derrol Nail, a NASA official, speaking from the naval base in Portland. “It was a beautiful sight, with the crew module making its way down to the ocean, and we watched the slow descent as it made its way towards the ocean.”

The navy boat was waiting as long as two hours for the ammonia to come out, before opening the capsule. Ammonia, lethal to humans when exposed to high levels, is used for the crew module’s cooling system, which is crucial for future crewed missions, Nail said.

In the months leading up to the capsule launch delays are still possible. The Artemis 1 mission was delayed by NASA due to an engine problem, a liquid hydrogen leak, and then a storm. The mission was launched on November 16.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Program: Design and Construction for the First Three Space Missions of the Artemis Generation, and Mission Expectation to Run by 2025

The lunar program, named after Apollo’s twin sister, hopes to revitalize some of the glory that NASA’s previous moon-landing missions amassed a half-century ago. An estimated 600 million people tuned in to watch the Apollo 11 landing in July 1969, when Neil Armstrong became the first human to walk on the moon.

“It seems fitting that we would honor Apollo with the new legacy of the Artemis generation and this mission today,” Catherine Koerner, deputy associate administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, said on Sunday.

NASA wants to get astronauts on the moon with the help of both the company’s human landing system and the capsule that comes with it. The contract was valued at over two billion dollars.

NASA’s inspector general, Paul Martin, said each of its first three flights will cost more than $4 billion, not including billions more in development costs. And by the end of fiscal 2025, NASA estimates it will have spent $93 billion on the Artemis missions.

“We’re paving a way to go on to not just the moon and Mars, but to establish a presence in our solar system beyond our home planet — to explore, to have those technologies in space, and to continue to learn and improve things here on planet Earth,” he said.