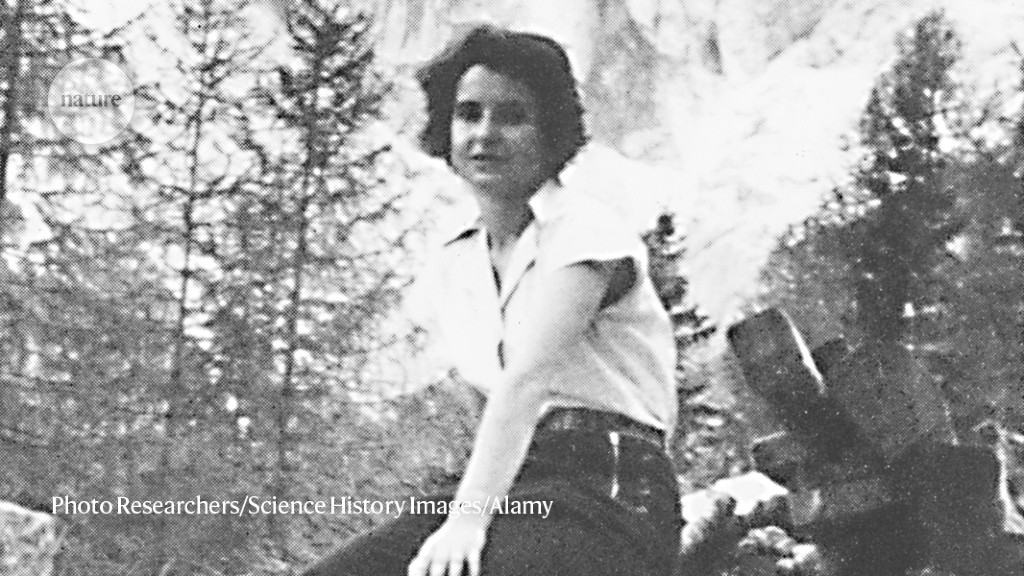

Untangling the DNA: Franklin and Wilkins used X-ray diffraction to study the structure of the pf DNA

One clear conclusion is that the untangling pf DNA’s structure was a team effort. Crick and Watson were the model builders, using cardboard cut-outs to show possible structures. They could not have arrived at the right structure without experimental data from Franklin and Wilkins.

Because of Watson’s narrative, people have made a fetish of Photograph 51. Franklin has become the symbol of both her achievement and what happened to her.

Franklin did not succeed, partly because she was working on her own without a peer with whom to swap ideas. She was also excluded from the world of informal exchanges in which Watson and Crick were immersed. Even though some at the time — notably the researchers at King’s and a small flock of what Watson called “minor Cambridge biochemists”16 — were not happy about Watson and Crick’s use of the King’s group’s data, the lead scientists at the Cavendish — Perutz, Bragg, John Kendrew — thought it was quite normal. There is no evidence to suggest that Franklin thought differently than he did.

In her contribution to the MRC report, Franklin had confirmed the 34 Å result for the B form. She said the unit cell of the crystal was huge and contained a larger number of atoms than any other unit cell. Franklin also added some key crystallographic data for the A form, indicating that it had a ‘C2’ symmetry, which in turn implied that the molecule had an even number of sugar-phosphate strands running in opposite directions.

In 1944, the microbiologist OswaldAvery and his colleagues discovered thatbacteria could be transformed into a form of disease by using their genes. It wasn’t clear that it was the genetic material in all organisms.

At King’s College London, biophysicists funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), and led by John Randall, with Maurice Wilkins as his deputy (who would later share the Nobel prize with Watson and Crick in 1962), were using X-ray diffraction to study the structure of the molecule. Franklin was using this technique in 1951 to investigate the structure of coal at the Central State Laboratory of Chemical Services in Paris.

With the Signer DNA, Franklin was able to exploit a discovery that Wilkins had made earlier — DNA in solution could take two forms, what she called the crystalline or A form, and the paracrystalline or B form. Franklin found that she could convert A into B simply by raising the relative humidity in the specimen chamber; lowering it again restored the crystalline A form.

Franklin concentrated on the A and Wilkins on the B forms. To a physical chemist, the crystalline form seemed the obvious choice. When it was X-rays in front of a photographic plate, it produced detailed, sharp patterns. More detail meant more data so the analysis was more difficult. The B form yielded more blurrier patterns that were easier to analyse. Franklin initially believed A and B to be two different things. In notes for a seminar she gave in November 1951, she described them collectively: “big helix with several chains, phosphates on outside, phosphate–phosphate interhelical bonds, disrupted by water”5.

So it was not a case of them stealing the King’s group’s data and then, voila, those data gave them the structure of DNA. Instead, they solved the structure through their own iterative approach and then used the King’s data — without permission — to confirm it.

The C2 symmetry was one of 230 types of crystallographic 3D ‘space groups’ that had been established by the end of the nineteenth century. Franklin didn’t appreciate its significance because she wasn’t familiar with it. Franklin said that she could have kicked herself for not realizing the structural implications, according to her colleague. The implications were realized because Crick had studied C2 symmetry intensely. But even he did not use Franklin’s determination of this symmetry when building the model; rather, it provided a powerful corroboration when their model was complete.

After Watson and Crick had read the MRC report, they could not unsee it. But they could have — and should have — requested permission to use the data and made clear exactly what they had done, first to Franklin and Wilkins, and then to the rest of the world, in their publications.