The Saharan Origins Revealed: Implications for the Connection to Other African Populations and the Exploration of Takarkori’s Ancient DNA

The origins of the Saharans were reconstructed using ancient DNA from two women that died in Libya around 7,000 years ago. The first full Saharan genomes from the African Humid Period, described in a study on 2 April in Nature1, reveal that the people were remarkably isolated from other African populations.

We used a function from theADMIXTOOLS 250 package to model Takarkori’s ancestral relationship with other populations. We used a function for automated graph exploration with a model that includes Mota, Iran Neolithic, Natufian, Taforalt, Takarkori and the outgroup chimpanzee. The model is compatible with small f-statistic residuals. The fitted graph suggests that Takarkori traces most of its ancestry (93%) to a hitherto unknown North African population, in agreement with the isolation signature obtained from the f4 statistics mentioned above (Fig. 3b). This unknown North African population is closely related to OoA populations and branches off the lineage leading to OoA later than the ancient individual from Mota Cave, Ethiopia, who represents the sub-Saharan African lineage most closely related to OoA groups identified so far. In our model, the remainder of the Takarkori individuals’ ancestry (7%) is derived from a deeply ancient Levantine source. The Neanderthal genes found in Takarkori correspond to the genes found in the Levantine Neolithic, aligning them with our estimates. The graph also models Taforalt as a mixture of a 40% contribution from a Takarkori-related branch and 60% from a Natufian-related branch, consistent with our qpAdm results (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Data 6).

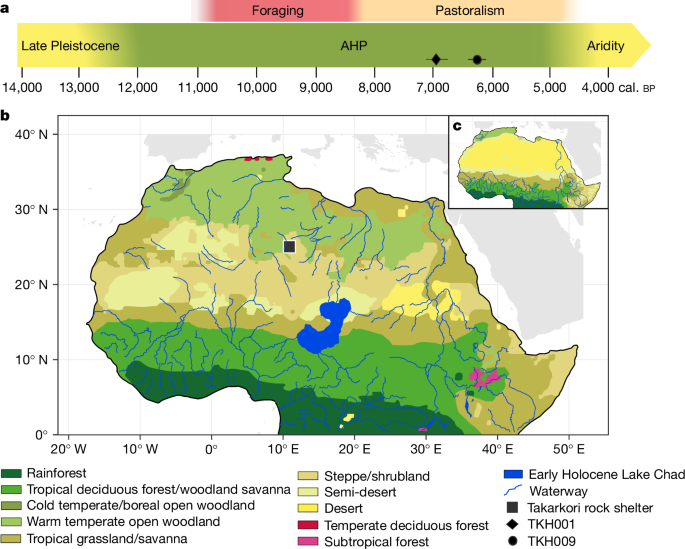

The Takarkori rock shelter is located in southwestern Libya. Between 2003 and 2007, archaeologists found the remains of 15 people who were buried at Takarkori between 8,900 and 4,800 years ago. The two corpses that had naturally mummified were women who lived between 7,000 and 6,000 years ago.

That’s why it’s important to explore sites that are protected from the elements, says Nada Salem, an archaeologist at the Max Plank Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

The Sahara Desert: Ancient Genomes in North Africa – the Challenge to Come and See What Ancient Genomic Genomes Can Tell Us about the Past, Present, Future and Future

The inhospitable landscape we know today is not the same as the Sahara Desert used to be. Between 14,500 and 5,000 years ago, the area was unrecognizable, transformed into a lush savannah by an unusually wet interval called the African Humid Period. People roamed this green landscape for thousands of years before it was again lost to sand.

There are difficult to come by ancient genomes from North Africa. Most of the palaeogenetic work is done in Europe and Asia. In the Sahara, high temperatures and strong ultraviolet light can quickly destroy ancient DNA.